A Legacy of Leadership: Joan Timeche Retires After 25 Years at the Native Nations Institute

After helping dozens of tribes across North America to strengthen their capacities for self-governance, the Hopi educator and long-time NNI Executive Director will complete her service at the University of Arizona at the end of the 2025 calendar year.

Before she was a nationally respected expert on Native Nation Building and Indigenous governance, NNI Executive Director Joan Timeche (Hopi) grew up near one of the most iconic vistas on Earth. But, for those living on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon year-round, life wasn’t all vacation.

Timeche’s parents worked for the Fred Harvey chain of hotels, which operated out of a handful of historic stone-and-wood buildings designed by storied architect Mary Colter. Timeche’s mother worked in housekeeping. Her father began as a bellman before moving into the painting department. “So if you ever go to the El Tovar Hotel…you're going to see huge murals in the dining room that were painted by my uncle,” Timeche said, “and my dad did paintings along the hotel hallways there.”

Fred Harvey actively recruited employees from the nearby Navajo and Hopi Reservations, which is how Timeche’s parents found their way to the company. She, her parents, three brothers and two sisters lived in employee housing which, at the time, was still segregated. “All of the Natives were in one housing area,” Timeche explains.

Life in the park meant being surrounded by an always-changing assembly of families from all over the country. So, Timeche says she was used to being a minority in her community, noting that many newcomers to the area had “never met any Native Americans” before coming to northern Arizona.

Despite living hours from their homelands, the Timeche family maintained close ties to the Hopi community. “My parents were really committed to making sure their parents had enough food to eat, and that they were well cared for,” Timeche said. “And, of course, we would take care of the farming that had to be done and participate in the ceremonies that were going on.”

When Joan was in primary grades, the roads between Tuba City and the Hopi Reservation were not yet paved. So, every weekend, the family would join with other Hopi workers to make the three-hour trip to the reservation, including more than an hour on unforgiving dirt roads, together. “Everybody would go in caravans on Friday evening,” Timeche said, “and we’d all try to make it up and down those mesas, particularly when it rained or it snowed, pulling each other up, getting the chains, men pushing cars that were stuck and stuff like that just to get out to the rez.”

As a child, this weekly routine seemed ordinary to Joan. But, later in life, she realized those moments were invaluable with respect to keeping her tethered to her community in ways she couldn’t yet understand. “It’s not until you're older that you begin to realize that time was special,” Timeche says.

Finding Confidence—and Motivation—in Competition

Though some of the students cycled in and out of the area as their parents were assigned to work at other parks or otherwise moved away, Timeche says she grew up with a consistent contingent of students “from kindergarten all the way to the 12th grade.” Her cohort was small, though – Timeche was one of just 25 students in her graduating class “and that was the biggest class they had ever seen,” she says.

Timeche excelled academically, joined school clubs and cheered on her brothers in sports. Still, she recalls a period of time beginning in middle school that helped her take her academic achievement to new heights.

A new superintendent took over operations at the national park and that official had a daughter who just happened to be the same age as Timeche.

“She’d never met any Native Americans,” Timeche explains, “and I didn't feel like I was treated very well by her. She snubbed her nose at me.”

This lit a competitive spark inside of Timeche. “There was academic competitiveness between us,” she said. But that rivalry turned out to be the nudge Joan needed to be the absolute best student she could be.

“I think for a long time she was my motivation to really push myself academically to prove that not all Indians were dumb,” Timeche said. “I was already headed down that road, but she really made me push a little bit more.” No surprise to anyone that knows her, but Timeche won that battle and was named valedictorian of her high school class.

Coming Home to Serve

Though she wasn’t quite sure what path to follow at the time, Timeche went to college at Arizona State University for one semester and transferred to Northern Arizona University (NAU) where she found herself majoring in social work. She was the first member of her family to attend a university.

In her junior year, a summer job as a youth counselor with her Tribe’s youth employment program rekindled Joan's desire to serve her Hopi community. It was, Timeche said, “a great opportunity for me to connect with other youth my age… and to be back out on the reservation again.”

After graduation, the Hopi Tribe Employment & Training Program hired Timeche even before identifying a specific position for her to fill. “They knew they wanted to hire me, but they didn't quite have a job for me,” she said.

She eventually became Assistant Director of the Hopi Education Department and, shortly after, its director. “I became the director very young,” Timeche said. “I was still really young, maybe three years out of college, and a female in a heavily male-dominated environment.”

One of her first assignments as Director of Education was to continue efforts to secure funding to build a new high school on the reservation so the community could keep more of its students on the rez rather than being forced to send them off to boarding schools.

But, where such a task in most American cities would be a matter of working with a municipal or county school district, funding for Tribal schools was handled by the Federal Bureau of Indian Education, and that meant going to Washington, D.C. to appeal directly to congressional and agency representatives for resources and support.

The work was something of a trial by fire. “A lot of times I felt like I didn't know exactly what I was doing. I had to talk to lots of folks, get input from them,” Timeche said, adding, “I think that's a lot of where my team approach really got cemented.” Later, as she reflected on her work experiences, Joan said that working for her tribe in a rural community with minimal resources required her to learn new skills and to be innovative, adaptable, resourceful, and self-reliant, all of which proved to be key attributes in her personal and professional endeavors down the line.

Those early years forged her belief that meaningful policy grows from broad participation—not solitary authority. “It just can't be one person. It has to be a team of folks working together to make the best decisions that we can,” she says.

Discovering Nation Building

After eight years as the Hopi Tribe’s director of education, Timeche returned to NAU to pursue her MBA. She worked at NAU’s Center for American Indian Economic Development during graduate school, later serving as its director. It was there that she first encountered two Harvard scholars whose research would alter the course of her future: Stephen Cornell and Joseph Kalt.

“When I first met Joe and Steve and listened to their research findings, I just thought ‘Oh, my gosh. When did these guys come out to Hopi?’” Timeche said. Though she was skeptical at first, Timeche says she quickly realized that there was something to this thing that Cornell and Kalt were calling “the Nation-Building Approach” to Indigenous governance. “I was just recognizing that what they had identified was what was happening on my reservation,” Timeche said. And, so, she started listening more closely.

NAU and the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development joined to create the National Executive Education Program for Native American Leadership (NEEPNAL). Her co-director at NEEPNAL was Manley Begay (Navajo), who would ultimately become the University of Arizona Native Nations Institute's (NNI) first director. Timeche sat in on a handful of professional development seminars led by Begay, Cornell and Kalt though she wasn’t leading them at this time. During those sessions, Timeche says she marveled as she witnessed Tribal leaders from Native nations all over Turtle Island experiencing the same epiphany she had. “If their heads were transparent, you could just see those wheels going,” Timeche said. “I was just in awe.”

This, of course, was the foundation of what came to be known as Native Nation Building, and it established the framework for Timeche’s next quarter-century of work.

Supporting Indigenous Sovereignty, One Community at a Time

At NNI, Timeche became known and respected for her ability to walk into places where colleagues were at odds with each other and help them to find common ground.

“There have been times where the tension in the room is so thick you could cut it with a knife,” Timeche says of some of her more difficult facilitation sessions with Tribal leaders, staff, and community.

But her method for diffusing that tension wasn’t magic. It was attention.

She learned to use “visioning questions” about the type of community Tribal nations wanted to create to set the stage for collaboration and to refocus groups on their shared goals for the future. When factions emerged mid-meeting, she reminded them of their common purpose. “They might say it a little bit differently, but ultimately they all want the same thing,” Timeche explains.

This approach, of course, arose from a lifetime of lessons in community building: trust can only be built through respect. “It comes down to just some real basic human relationships,” Timeche said. “How you treat each other is going to really determine the level of success in any relationship.”

Legacy, Impact and Advice

Though she hasn’t kept an official tally, by all accounts Timeche has worked with and traveled to dozens of (and likely more than a hundred) Native nations. “Maybe I’ll count them up after I retire,” she joked. Throughout that time Timeche says the work she’s done in community has always inspired her.

“Sometimes I'm just amazed by what people will come up with,” Timeche says of her Nation-Building seminar participants. “There are really good, hardworking people out there – smart people, thoughtful people that really want to have a solid community.”

And, Timeche says, seeing communities plan their futures and getting the opportunity to participate in that process has brought her deep personal satisfaction.

“It just gives you hope,” she says of seeing people engaged in the process of uplifting their communities. “We (NNI) are not going to be doing the actual implementation ourselves, but we get to leave knowing that we’ve played that little sliver of a role over time and that's one thing I know I will miss.”

As she steps away from her role, Joan shares a simple message for the next generation of leaders at NNI: “Listen and learn before you start pulling levers.” She says she hopes decision makers “understand how important the role that NNI has played for Native communities over the years” and that they “really utilize the expertise of the staff, the stakeholders and the beneficiaries” when planning for the next phase of service to Native nations.

For Native youth, her advice is timeless: “Be curious and pay attention,” Timeche says. She encourages young people to ask questions and to notice who makes certain decisions and why. “Learn the stories behind ceremonies, relationships, and responsibilities,” Timeche says. “Eventually, they always end up coming back together again and helping you to better understand the environment that you're in.”

Though she will be leaving the U of A workforce, Timeche doesn’t plan to slow down entirely after retiring. Once an avid golfer, Timeche says she plans to travel the country to play on as many Tribally owned golf courses as she can.

It’s a fitting next chapter for an educator who has spent her life helping Native nations envision and build the futures they want to see for their communities, and who approached every day, every task thoughtfully, collaboratively, and always with deep respect for the people she serves.

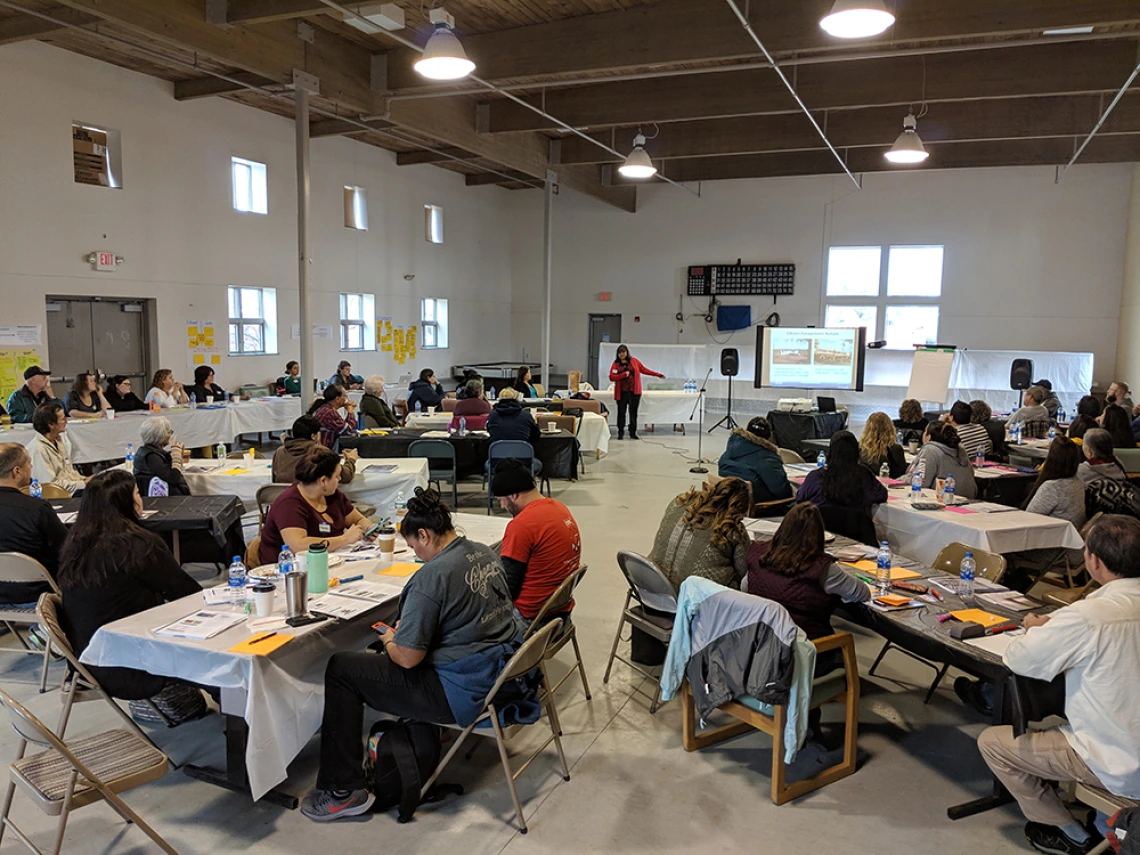

Photos from Joan's retirement celebration "A Legacy of Leadership" and NNI's International Advisory Council meeting on Dec. 4, 2025.